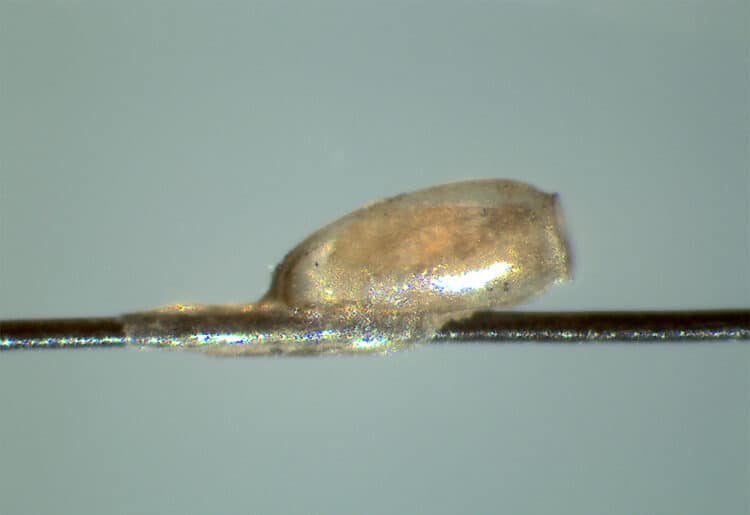

SCIENTISTS at the University of Reading have discovered that human DNA can be extracted from the cement-like substance head lice used to glue their eggs to hairs thousands of years ago.

It is thought that this discovery will provide an important new window into the past.

In a new study, scientists recovered DNA from mummified remains that date back 1,500 to 2,000 years.

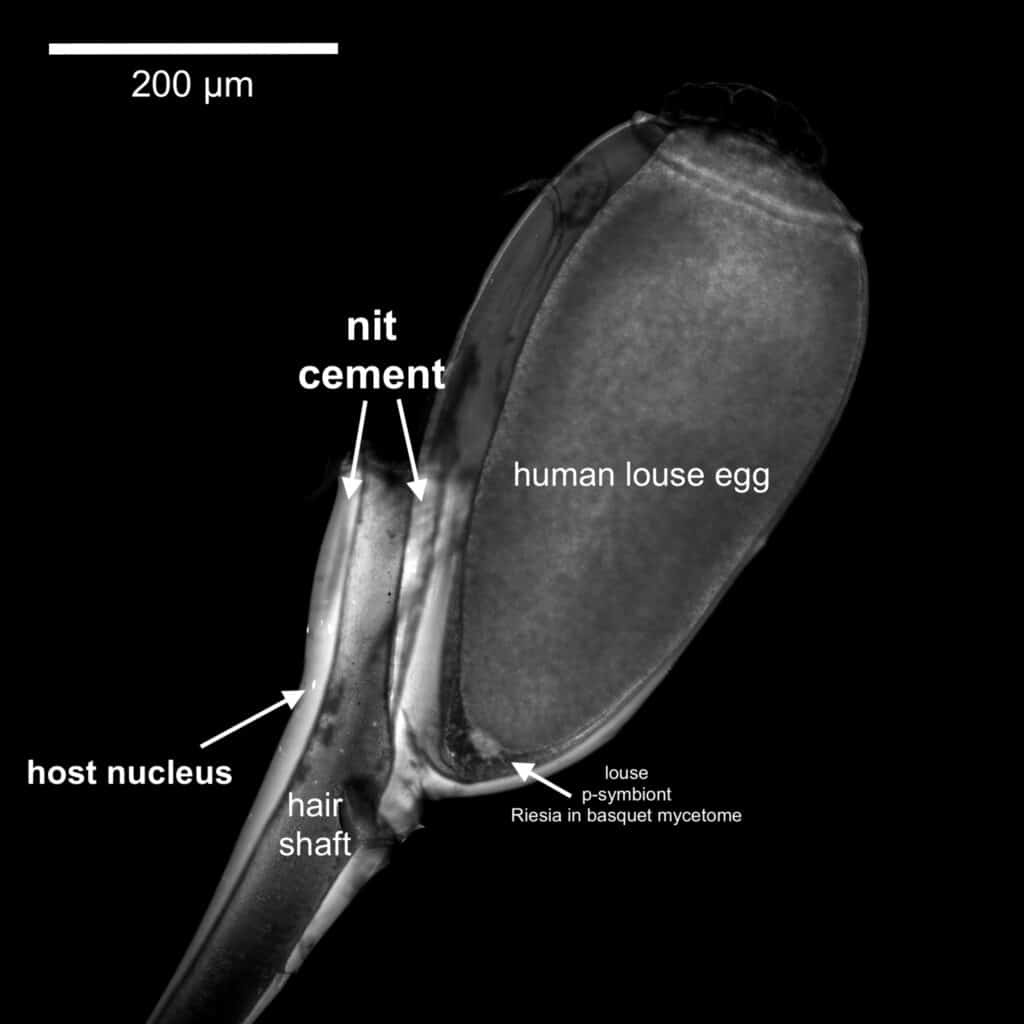

This is possible because skin cells from the scalp become encased in the cement-like substance produced by female lice as they attach eggs, known as nits, to the hair.

Analysis of this newly-recovered ancient DNA has revealed clues about pre-Columbian human migration patterns within South America.

It is hoped that this method could allow many more unique samples to be studied from human remains where bone and tooth samples are unavailable.

The research was led by the University of Reading, working in collaboration with the National University of San Juan, Argentina; Bangor University, Wales; the Oxford University Museum of Natural History; and the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

It has been published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Dr Alejandra Perotti, associate professor in invertebrate biology at the University of Reading, led the research.

She said: “Like the fictional story of mosquitos encased in amber in the film Jurassic Park, carrying the DNA of the dinosaur host, we have shown that our genetic information can be preserved by the sticky substance produced by headlice on our hair.

“In addition to genetics, lice biology can provide valuable clues about how people lived and died thousands of years ago.”

Dr Perotti said that more researchers are looking into migration and diversity in ancient human populations.

“Headlice have accompanied humans throughout their entire existence, so this new method could open the door to a goldmine of information about our ancestors, while preserving unique specimens,” she explained.

Until now, ancient DNA has mostly been extracted from dense bone from the skull or from inside teeth, as these provide the best quality samples.

However, this can cause severe damage to the specimens which compromise future scientific analysis.

It is also against cultural beliefs to take samples from indigenous early remains.

Recovering DNA from the cement-like substance delivered by lice provides a solution to this problem.

Dr Mikkel Winther Pedersen from the GLOBE institute at the University of Copenhagen, and first author, said that the high amount of DNA yield from the nit cements came as a surprise.

“It was striking to me that such small amounts could still give us all this information about who these people were, and how the lice related to other lice species but also giving us hints to possible viral diseases,” he added.

As well as the DNA analysis, scientists are also able to draw conclusions about a person and the conditions in which they lived from the position of the nits on their hair and from the length of the cement tubes.

Their health and even cause of death can be indicated by the interpretation of the biology of the nits.

Analysis of the recovered DNA revealed a genetic link between three of the mummies and humans in Amazonia 2,000 years ago.

This shows for the first time that the original population of the San Juan province migrated from the land and rainforests of the Amazon in the North of the continent, south of current Venezuela and Colombia.

It also found the earliest direct evidence of Merkel cell Polymavirus.

The virus, discovered in 2008, is shed by healthy human skin and can on rare occasions get into the body and cause skin cancer.

The discovery opens up the possibility that head lice could spread the virus.