The work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was the subject of Jane Burrell’s presentation to Wargrave Local History Society in April.

She represented the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation, part of the MacRobert Trust, which provides education on the work of the Commission.

The Trust had been established by Lady MacRobert, following the loss of her three sons in quick succession whilst serving in the RAF during the Second World War. Her response had been to donate £25,000 to buy a bomber for the RAF – to be known as “MacRobert’s Reply” – a tradition still maintained.

Before the First World War, those who died on active service were normally buried in common graves, not marked with the names of the deceased. However, in 1914, Fabian Ware, working for the Red Cross unit in France, became concerned at the lack of recognition of the burial places, often lost as the trenches of warfare moved to and fro.

He set about recording the names and locations and, by 1915, gained recognition of the War Office, and the support of the then Prince of Wales.

This led to the formation of the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1917, with Fabian Ware in charge.

He established its principles, based on of equality of treatment – irrespective of rank, creed or colour, the body would be laid to rest close to the place where they died.

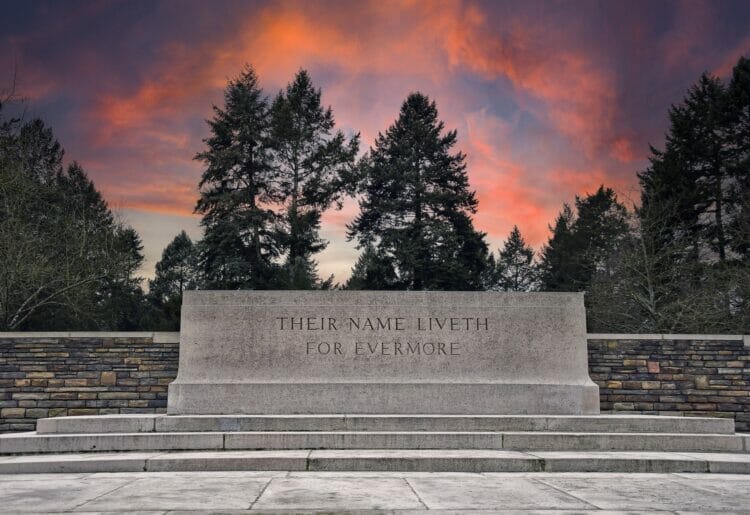

The markers are of a standard style, usually made of Portland stone, with a religious symbol, the name, rank and date of death (where known), and a short personal inscription if the family wished it.

For those with no identifiable grave, there were large memorials with stone panels listing each of them.

In addition, as it was recognised that many of the family members of the deceased would not be able to visit these overseas memorials, memorials such as the Cenotaph in Whitehall were also created.

The CGWC looks after these memorials, worldwide, ensuring the names are kept legible in perpetuity, the grounds tended, and records maintained of each of them.

With 1.7 million Commonwealth casualties to be commemorated, the size of the task is immense.

Jane’s husband, Philip, then showed how to research those who are remembered in this way, using the names of casualties recorded on Wargrave’s village memorial for his examples.

PETER DELANEY