A TEAM of scientists using a NASA telescope to look into deep space have captured images of activity in the magnetosphere of Neptune for the first time.

A project led by researchers at Northumbria University and including an expert from the University of Reading have used the James Webb Space Telescope to observe the activity, a newly-published study explains.

Disturbances in a planet’s magnetosphere–the area around a planet where charged particles are affected by the planet’s magnetic field–by solar winds are known as auroras.

Energetic particles expelled by the sun are trapped in this field, striking the upper atmosphere and creating a glowing effect.

These disturbances are visible to the naked eye on Earth, known as the Northern and Southern Lights, but researchers have now captured images of similar activity around Neptune.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, used data collected by the James Webb telescope to capture the images of activity which hasn’t been observed since 1989.

Scientists obtained data in June 2023 that revealed the presence of trihydrogen cation (H3+), which is a clear marker of auroras.

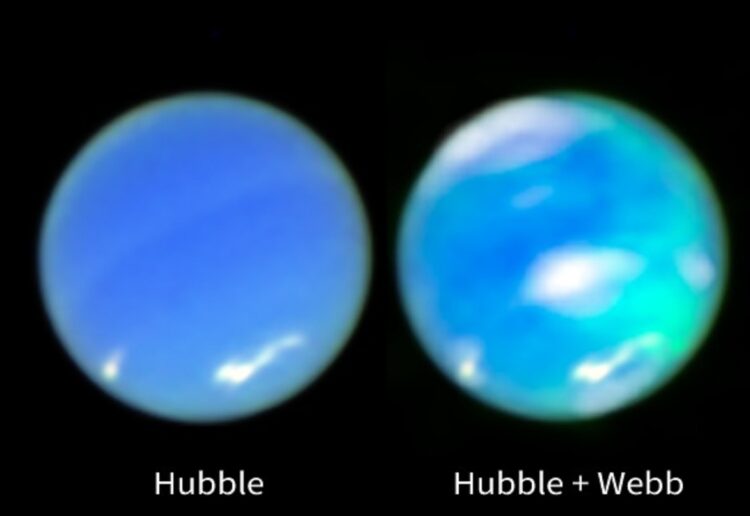

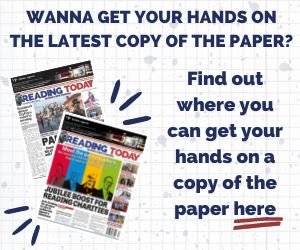

In Webb’s images, Neptune’s auroras appear as cyan-coloured spots, and, unlike Earth’s auroras which appear at the poles, Neptune’s auroras are located at mid-latitudes.

These would be roughly equivalent to where South America is located on Earth; this is due to its unusual magnetic field, which is tilted 47 degrees from its rotation axis.

The Webb observations also showed Neptune’s upper atmosphere has cooled dramatically since 1989, with temperatures just over half of what they were then.

This explains why the auroras remained hidden for so long, as colder temperatures result in much fainter auroras.

This cooling is particularly surprising, scientist say, as Neptune sits over 30 times farther from the sun than Earth.

Scientists now plan to study Neptune over a full 11-year solar cycle to better understand its bizarre magnetic field and atmospheric changes, potentially revealing why its magnetic field is so unusually tilted.

Dr James O’Donoghue co-authored the study from the University of Reading.

He said: “Nobody has seen Neptune’s auroras since 1989, despite our team’s best efforts using the world’s largest telescopes–it has been a real head-scratcher. Thanks to the sensitivity of the James Webb Space Telescope, we’ve finally found it.

“What’s most exciting to me is that we can even measure its temperature.

It turns out that Neptune has cooled by hundreds of degrees since 1989, which means it now emits just 1% the amount of light it did more than three decades ago. This explains why it has been impossible to detect until now.”