A FOSSIL discovered by a professor at the University of Reading could be an entire dinosaur skeleton giving insights into how the species developed as excavation gets underway.

Academics, including a number of university students, are working to uncover the find in Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada.

It was first discovered in 2021 during a field school scouting visit, led by Dr. Brian Pickles, an associate professor teaching zoology and palaeoecology at the University of Reading.

His team was conducting a search of an area when a volunteer crew member, Teri Kaske, noticed part of the fossilised skeleton sticking out of the hillside.

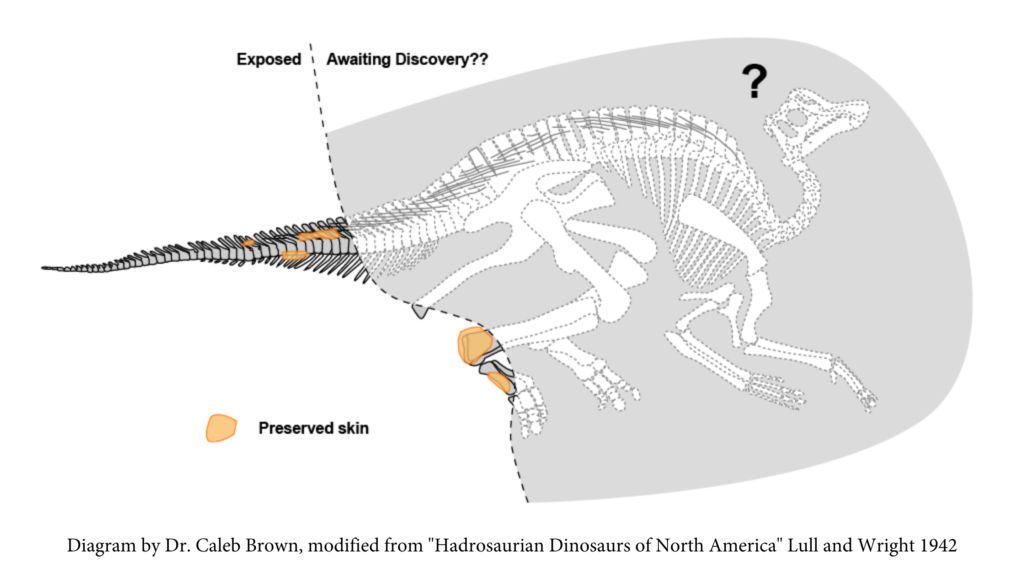

A large portion of a tail, as well as a right hind foot, were uncovered, and the orientation of the bones in the hillside has led academics to suggest that an entire skeleton, complete with preserved skin, could be present.

Finding fossilised skeletons whole is exceptionally rare, but the site is a particularly rich one for finding dinosaur fossils, leading to its name of Dinosaur Provincial Park.

The dinosaur “mummy” is believed to be the remains of a hadrosaur, which is described as a large-bodied, herbivorous, duck-billed dinosaur.

Skeletons in their entirety, especially complete with skulls, can give important insights about the species, and juvenile specimens can also lend insight into their development.

Now, as part of the first international palaeontological field school, teams from the University of Reading, the University of New England, Australia, are working to excavate the fossil so that it can be preserved.

They’re working in collaboration with the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada, where the fossil will be processed and uncovered by skilled specialists.

Dr. Pickles said: “This is a very exciting discovery and we hope to complete the excavation over the next two field seasons.

“Based on the small size of the tail and foot, this is likely to be a juvenile.

“Although adult duck-billed dinosaurs are well represented in the fossil record, younger animals are far less common.

“This means the find could help palaeontologists to understand how hadrosaurs grew and developed.”

Dr Caleb Brown, from the Royal Tyrrell Museum, said: “Hadrosaur fossils are relatively common in this part of the world but another thing that makes this find unique is the fact that large areas of the exposed skeleton are covered in fossilised skin.”

“This suggests that there may be even more preserved skin within the rock, which can give us further insight into what the hadrosaur looked like.”

The excavation and collection of the fossil is expected to take months to complete.